Cross-posted at Luna Station Quarterly.

“My daughter can spin straw into gold.” The miller’s boast captures a king’s interest and the innocent, ordinary girl must do the impossible—or die.

“My daughter can spin straw into gold.” The miller’s boast captures a king’s interest and the innocent, ordinary girl must do the impossible—or die.

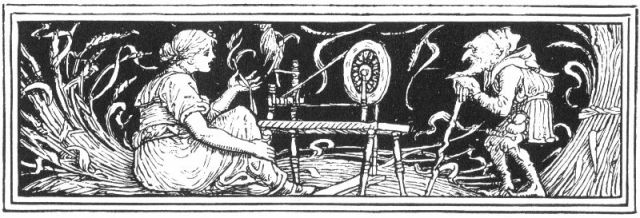

“Rumpelstiltskin,” as told by the Grimms in 1812, is a familiar story whose origins go back hundreds of years. In variants, such as the British “Tom Tit Tot,” the daughter spins an inhuman amount of straw into string—no mention of gold. Still, an impossible task. The impossibility makes room for the appearance of magic in the form of a diminutive, wily—some might say demonic—man who fulfills the bargain, thereby rescuing the girl, though he extracts an equally inhuman price in the form of her first-born child.

As Tracy Cochran, editor of Parabola Magazine, says in her essay “Spinning Straw,” “Most humans know how it feels to be in this impossible situation, desperate to spin something shiny, gold, full of the doomed sense that we must do more and be more than we really are.”1 But is this the heart of the story? Fairy tales, given they are steeped for hundreds of years, shared in intimate settings—at the bedside, as the spindle whorls—are nuanced things, embracing our dreads, hopes, dreams, furies, joys—everything about us, even our history. And the spinning of yarn, so significant to our cultural development that spin has become a synonym for create, parallels the history of domestic womanhood.

The miller’s daughter is set a task that is beyond her powers to achieve. This is one way to comprehend the fairy tale “Rumpelstiltskin.” Another way is to expand the borders of the story, peek behind the curtain at the girl before her father’s boast: there she sits, at the spinning wheel beside the fire, flax on the distaff, fingers flecked with the cuts and blisters of a day’s work. But she’s not alone. Her grandmother, resting in a chair nearby, tells a story her grandmother told her that was told by her grandmother, and so on.

Before the miller’s boast to the king, he reveals his longing at the local tavern. “My good daughter’s so willing I be rich, she’s spinning twice the yarn in half the time.”

The baker, rather than reveal his doubt, slams his tankard on the table, saying, “What a good idea. I have two daughters—imagine the feast I’ll have when they double their keep.”

Not to be outdone, the miller resolves to keep his daughter up all night. What happens next, when, staggering home in the morning, the miller inadvertently meets the king, is a tale we know.

Prior to the rise of cities, most people lived in small agricultural settlements in which women wielded both the spade and the spindle. It was women’s work to keep everyone fed and clothed, and it was within their power to decide how, when, what, and even why it should be done.

With the spinning wheel, which arrived in the West via India and China in the thirteenth century, came the ability to overproduce yarn, leading to beyond-sustenance gains falling into the outstretched hands of the menfolk. In time, spinning became a cottage industry employing whole families. With industrialization, entire communities were virtually enslaved in the woolen mills, having no control over the how, when, what, and why of production.

Perhaps the miller’s daughter, weeping alone in an attic room, surrounded by mounds of flax that must be spun somehow into gold, was paralyzed not only by fear but by the usurpation of her job, her identity—her self.

Spinning is a birth process, a life process, and its story—its yarn—is what binds us, literally and figuratively.

Image Credit: Walter Crane [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Cochran, Tracy. “Spinning Straw.” Parabola Magazine, accessed October 23, 2017, https://parabola.org/2017/07/30/spinning-straw-by-tracy-cochran/

- Close-Hainsworth, Freyalyn. “Spinning a Tale: Spinning and Weaving in Myths and Legends. Folklore Thursday, accessed October 22, 2017, http://folklorethursday.com/folklife/spinning-a-tale/#sthash.cYg84l0e.dpbs

I hope you enjoy the video featuring Renate Hiller who says, among other things, “When we twist fibers into yarn, we are actually creating a spiral, and the spiral is a cosmic gesture of creation.”