One day, when my daughter was about four years old, she said, “My breath speaks to me.” I was amazed by the ancient wisdom implied in this adorable insight.

Breath, wind, wisdom and genius have long been associated with one another, in religion and mythology, in fairy tales and poetry.

Who has seen the wind?

Neither I nor you:

But when the leaves hang trembling,

The wind is passing through.Who has seen the wind?

Neither you nor I:

But when the trees bow down their heads,

The wind is passing by.(“Who Has Seen the Wind?” by Christina Rossetti)

Wind’s matrix is air, which lives within and around us, at all times. It can whisper, howl soulfully, and sometimes roar like the fiercest dragon. Personified, it is male or female, young or old, nasty or well meaning. As a numinous entity, it has long been associated with the universal life force—prana and chi, for example.

Wind, in most religious and mythological connections, represents spiritual power, which is why we use the word inspiration. In the Whitsun miracle the Holy Ghost filled the house like a wind; spirits make a kind of cold wind when they come, and the appearance of ghosts is generally accompanied by breathings or currents of wind.1

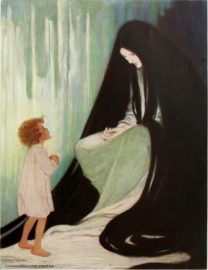

It is the spiritual significance of cold wind, in particular, that gives the north wind a predominant role in western fantasy and fairy tales. In his ground-breaking book At the Back of the North Wind, a tome that influenced C.S. Lewis a generation later, Scottish pastor and author George MacDonald conjures a tale of a poor, humble coachman’s son named Diamond whose pure heart makes it possible for him to see the North Wind, personified as a beautiful, long-haired lady, sometimes very small when the wind is tame, but often large, powerful and dangerous.

She carries Diamond around the world and he watches while she goes about her business, an invisible force offering reward or punishment, as deserved. Critics of the novel have pointed to MacDonald’s Christianity as evidence that he uses the story of Diamond to preach the gospel. However, the North Wind is as much Kali as she is Holy Spirit; some have even referred to her as death personified. Her sibylline nature is, perhaps, the point.

The north wind also figures in “The Selfish Giant” by Oscar Wilde, the Norwegian fairy tale “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” and in Aesop’s fable “The North Wind and the Sun.” One fairy tale casts the north wind in a central role.

“The Boy Who Went to the North Wind” is the story of a poor child whose grain is snatched by the North Wind several times before he finally journeys to the trickster’s home to complain. The North Wind admires the boy’s determination and humility and rewards him with access to unlimited food via a magic tablecloth. An innkeeper steals the cloth, but the North Wind proves to be a steady friend and provides a magic ram in its place. The innkeeper steals that, too. The North Wind then slyly gives the boy a magic stick with which to punish the greedy innkeeper who then returns the stolen items.

Under special circumstances, wind takes the geometric form of a torus, becoming a tornado. Perhaps the most potent literary example of a tornado’s symbolic strength is in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a book that can be described as both fantasy and fairy tale, and a rare early twentieth-century example of the heroine’s journey.

Dorothy is a young girl living in the heart of the Kansas prairie with her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em who are farmers eking a living from the cracked, dry, colorless landscape. Life is hard.

When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now.2

Tornadoes have been known to lift objects and carry them for miles. Just so, Dorothy is alone in the house when one strikes, carrying her to a new land, one where she will be tested nearly beyond endurance, and where she will ultimately prevail. On her return home, Dorothy is wiser, stronger.

A woman must practice calling up or conjuring her contentious nature, her whirlwind, dust-devil force. The symbol of the whirling wind is a central force of determination which, when focused rather than scattered, gives tremendous energy to a woman.3

Did Dorothy, bored out of her mind and desperate for change, call forth the tornado? Did a lonely boy summon the North Wind?

The answer to these questions, and more, might be closer than your next breath.

(Cross-posted at Luna Station Quarterly)

First Image Credit: Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons

Second Image Credit: Comfreak at Pixabay.com

- von Franz, Marie Louise. The Interpretation of Fairy Tales (Shambhala: Boston, 1996), 68.

- Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Grosset & Dunlap: New York, 1963), 2.

- Pinkola Estés, Clarissa. Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype (Ballantine Books: New York, 1992), 61.